Merging boundaries: Sung Hwan Kim at the Van Abbemuseum

Combining video installations, collage, music, performance, sensorial elements and spatial design, Sung Hwan Kim creates poetic worlds through innovative storytelling. Spread across ten rooms at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, his current exhibition invites visitors to reflect on their relationship with borders and migration. Minsun Kim visits the exhibition and sits down with the artist to discuss his work.

The work of Sung Hwan Kim (1975, Seoul, currently based in Hawai’i and New York) primarily revolves around film. In installations that utilize architectural elements and feature poetical drawings, Kim connects his films to the surrounding space, integrating both music and live and filmed performances. Currently, his solo exhibition is on view at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, featuring works made over the past twenty years, curated by Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide. The title of the exhibition, Protected by roof and right-hand muscles, is borrowed from the lyrics of musician and composer David Michael DiGregorio (aka dogr), a long-time collaborator of the artist. I attend the opening of the exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum, which is accompanied by a musical concert. After spending some time in the exhibition, I sit down with the artist for a conversation about his work.

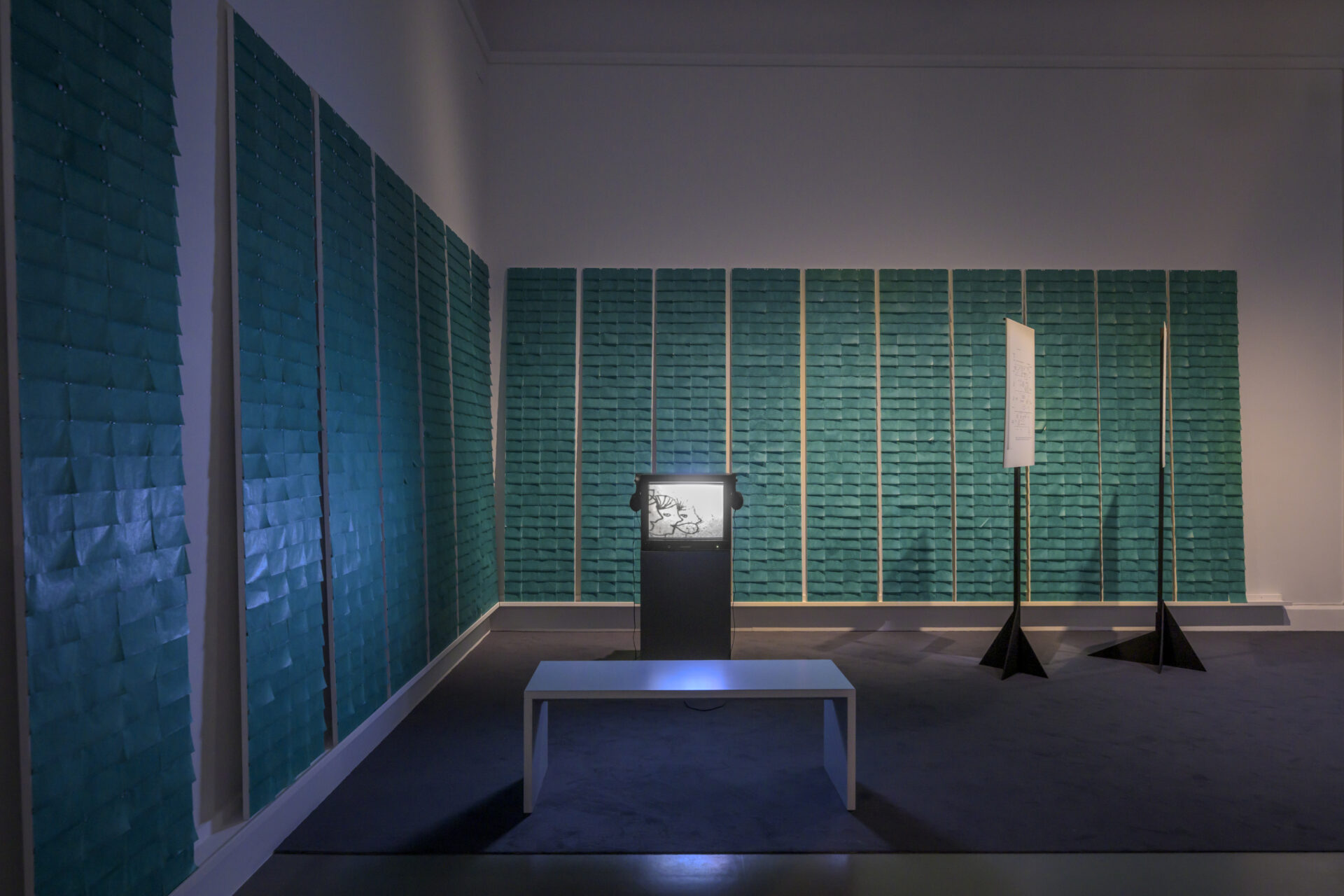

The exhibition is Kim’s largest solo show to date. The public trajectory of the exhibition began during Kim’s residency and open studio project, Overhauled Stories, at Framer Framed in Amsterdam last summer. During the open studio, Kim revisited his early creations, focusing on reframing three of his earlier video installations by exploring the potential for reconfiguring their existing elements. The exhibition features ten of Kim’s most significant films and videos presented in architectural installations, as well as drawings and photographs, spread across ten gallery rooms. In the exhibition, the artist takes on the role of a spatial designer. His architectural elements completely dismantle and reassemble the white cube space, producing a poetic and sensory sense of drama through lighting and sound. This is a distinctive feature not only within the realm of the spatial design, but also in the blurring of the boundaries between various mediums in Kim’s works. Departing from attempts to separate different mediums into distinct or traditional categories, Kim’s work extends from film to installation, blurring the boundaries between the two, and sometimes suggesting that elements of installations are doors entering into the story told within the film.

It becomes clear that the diversity of viewpoints in- and outside the videos is a deliberate artistic intervention, granting an additional layer of meaning to the works

Human scale

At the Van Abbemuseum, Kim’s films and videos are projected on screens of different sizes. Temper Clay (2012), for example, is projected on a relatively large screen hanging from the ceiling. As a result, the audience maintain a distance from the screen and are made to look higher than the usual eye level. In this position, a contemplative witnessing seems more appropriate than a straight-forward consuming of the spectacle. Other works, like Dog Video (2006), are projected on smaller screens placed on the floor, requiring the audience to sit closer to the screen, creating a more intimate storytelling experience. Considering that Dog Video metaphorically portrays Kim’s relationship with his father and captures the subject from a lower perspective to express a certain hierarchy, it becomes clear that the diversity of viewpoints in- and outside the videos is a deliberate artistic intervention, granting an additional layer of meaning to the works.

The variations in height and distance prompt a reflection on the human scale and induce movements in the body while present in the exhibition space. Kim frequently incorporates substitute metaphors into his work, some of which reappear in different films, including objects and performers such as DiGregorio and Kim’s niece, Yoon Jin Kim. Similarly, the Hyundai apartment complex in Seoul also makes appearances in both Temper Clay (2012) and From the commanding heights… (2007). As the exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum displays most of his films, extensive drawings, and collages, the repetitive metaphors in the different works refer back to each other, becoming a metaphor of the metaphor, thereby sparking new possibilities of dialogue between them.

During the opening concert of the exhibition, DiGregorio performed a song featuring the words 나는 공산당이 싫어요 (I hate the communists), a phrase in Korean that also featured in the film Washing Brain and Corn (2010), which was also presented in the show. During the concert, Kim positioned himself among the audience. Whenever the lyrics ‘I hate the communists’ echoed in Korean, several people in the audience simply understood the phrase in Korean, some perhaps due to the anti-communist education of their generation, while other audience members couldn’t grasp or understand the language. As the concert progressed, DiGregorio traversed the audience, repeatedly approaching random individuals to create a fade-in and fade-out effect. The unclear line between performer and audience mirrored the uncertain divide between Kim and DiGregorio, who during the concert seemed to replace the artist as taking centre-stage. In this sense, the physical arrangements of the concert mirrored many of the works in the exhibition, by merging cultural, linguistic, and generational boundaries.

Deferring certainty

The first room I enter features Kim’s latest project, A Record of Drifting Across the Sea (2017-), which delves into the unrecorded history of Joseon Dynasty immigrants to the United States in the early twentieth century via Hawaiʻi.[1] Through films, books, installations, and documentation material, this project unfolds various narratives at the same time. The first chapter of the project, Hair is a piece of head (2021), marks the first film series produced in Hawaiʻi, commissioned by the GB Foundation on the fortieth commemoration of the Gwangju Uprising.[2] The title, Hair is a piece of head, has a twisted meaning in Korean. Despite the existence of distinct Korean words for ‘hair’ and ‘head’, there’s a linguistic habit of using ‘head’ instead of ‘hair’. The film mentions the statement made by traditionalist Choi Ik-Hyun, who refused a haircut to modernize himself during the late Joseon Dynasty era, saying, ‘I would rather have my head cut off than cut my hair’. The implication of that statement is that, since hair is inherited from parents, it’s as precious as one’s own life. This memory of aphorism persists in the education of Koreans about Confucian values, viewing hair as an extension of the head, sparking questioning about tradition and education that enabled such (nonsense) logic. It raises the question of where to draw boundaries, extending uncertainties about where the boundary lies between head and hair, pushing further into questioning what belongs to oneself and others, as the artist explains.

As this example shows, Kim’s work is not easily graspable. It has many layers that do not always fit into a clear linear narrative. Instead, the work is deeply embedded in cultural and historical research, and as such functions more as a collage, a non-linear and polyphonic way of conveying a narrative. The films are spoken in English, Korean, Mandarin, and Hawaiian by different voices with the intention to, as Kim explains, ‘weave together the different subjectivities embedded in different languages.’ Audiences are not confronted with mere void spaces when encountering an unknown language or unfamiliar history. Rather, it’s a simultaneous visualization of knowing and not knowing, offering the potential to view what one believes they know from different positionalities.

Moreover, since contemporary artists working on an international scale often transcend national borders both physically and in their artworks, their work could be viewed as a form of borderless, non-nationalistic trade. Kim himself refers to this as ‘fabrication’. Sometimes, the artist positions works created through commissions obtained from financially capable spaces in locations where substantial commissions aren’t feasible. In those situations, the artist functions as a mediating channel, enabling, connecting, and forging new relations and systems. Kim seems deeply interested in the meta-context and those processes beyond the framing of artworks, and his consciousness of ‘fabrication’ inevitably extends to how he creates narratives within his work as well.

Pushing against the border

One of the recurring themes in the exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum is migration, a topic that rarely serves as a main topic in exhibitions organised in South Korea. Although Kim’s work is exhibited in South Korea quite often, there is a significant difference in how his works are interpreted inside or outside South Korea, reflecting how the boundaries and identities related to the concept are shaped from an external standpoint, influenced by where artists and their work stand. Although immigration issues certainly exist in South Korea, they don’t cause much controversy at a public level, given that the country primarily defines itself based on a single ethnicity. Consequently, the notion of migration isn’t something anticipated to be the focal point of exhibitions featuring ‘homegrown’ artists in South Korea. Many Korean artists initially seek a Western art education and later engage onto the global stage of contemporary art. Their artistic practices often stem from their immigrant experiences — whether diasporic or cosmopolitan — and may not necessarily align with their country’s public interests.

When reaching out to Kim to organise a conversation about his work, I asked him if we could have a dialogue in Korean. It was evident that I proceeded the conversation with him by heavily relying on our shared nationality. I asked the artist why he seems to stay clear of taking a clear political stance in his work. Kim explained the paradox that while the eye can perceive everything, it cannot see itself. Considering the possibility that many contemporary crises might have arisen from misconceptions about the relation between oneself and others, discussing ‘identities’ such as those based on nation-hood, always leads to inevitable exclusion. If one aims to firmly establish the ‘self’, one can’t help but frame the ‘other’ as a prerequisite. Therefore, Kim refrains from directly speaking politics while ensuring his work is inherently political. For him it is a case of remaining ethical, acknowledging both sides of each coin, still departing from a sense of self, but trying to refrain from othering the others.

With today’s tumultuous global political landscape which is marked by polarisation and advancing extremes, any people find themselves navigating a complexity of interpretations like never before. Many media trigger us with fragmented imagery, evoking quick sympathies. However, instead of hastily passing judgment, there’s a call to embrace this intricate tapestry alongside unspoken emotions, diverging from the prevailing societal doctrines. Kim scrutinizes the sense of the present in Hair is a piece of head, using a live photo function that captures the stretched spectrum of ‘now’. Additionally, the work is situated at the forefront of an art space, a contemporary art museum, inviting us once again to reconsider our perception of the present. Kim’s exhibition, filled with many time-based works, regenerates a sense of stillness compared to the instant consumption of contemporary media. This impending time isn’t solely the artist’s — it’s the individual viewers confronting their ‘nows’, challenging our fluid boundaries once more.

[1] The Joseon Dynasty, from the late 14th to the late 19th century, shaped the Korean Peninsula’s history.

[2] The Gwangju Uprising was a democratic movement in South Korea during May 1980, marked by citizens protesting against martial law, advocating for democratization, and facing violent suppression by the military.

The exhibition ‘Sung Hwan Kim: Protected by roof and right-hand muscles’ will be on view at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven until 26.5.2024. For more information, visit the website of the Van Abbemuseum.

Minsun Kim

is an artistic research-based practitioner