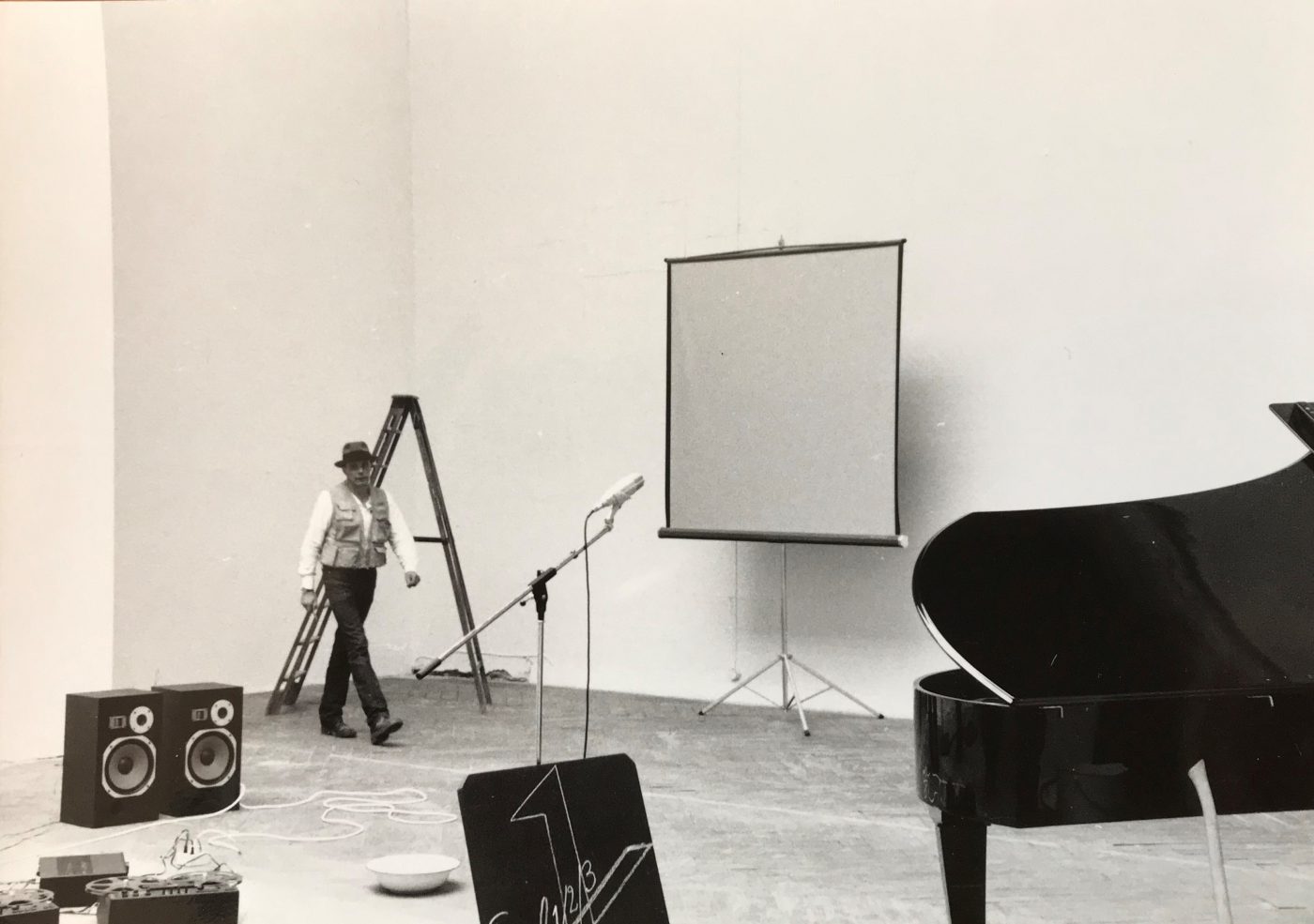

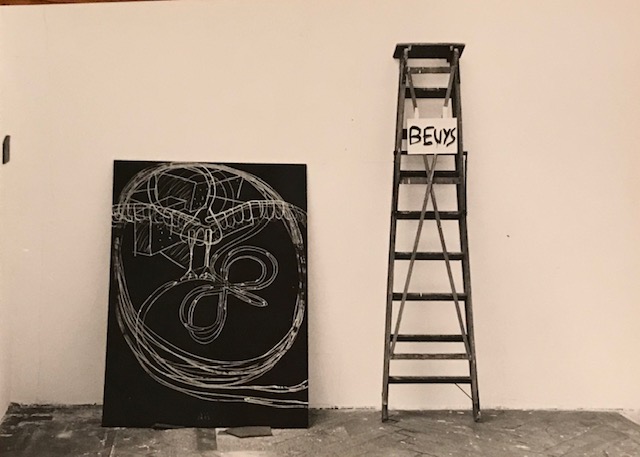

Joseph Beuys, Das Kapital Raum, Biënnale van Venetië, 1980, foto Pieter Heijnen

Shaman, artist and politician – remembering Joseph Beuys [EN/NL]

Today, May 12th, is the 100th birthday of Joseph Beuys. In Germany, they are celebrating this “Beuys Year”, including many exhibitions, especially in museums just over the border from The Netherlands, where he lived and worked. Beuys had an enormous influence, not only within the art world, but also outside of it. As an artist, he was one of the founders of the German political party “Die Grünen” (The Green party). A former student of Beuys’, Pieter Heijnen shares his first hand experiences and understanding of the artistic work of this major artist, who is at risk of unjustly fading into the background.

Dit jaar zou Joseph Beuys honderd jaar zijn geworden. Het wordt in Duitsland groots gevierd met een Beuysjaar, vooral in de musea niet ver van Nederland, net over de grens. Beuys’ invloed was enorm, niet alleen binnen, maar ook buiten de kunst. Hij stond als kunstenaar aan de wieg van de Duitse politieke partij Die Grünen. Pieter Heijnen, oud-leerling van Beuys, vertelt uit eerste hand over een kunstenaarschap dat ten onrechte wat op de achtergrond dreigt te raken.

–SCROLL VOOR NEDERLANDSE VERSIE–

“And once the tree grows tall, the planter will be long gone.” He says this with a laugh, in April 1982 in the town of Kassel, as he and a team of collaborators dig holes in the earth to receive the trees for his large scale piece, 7000 Oaks. All over town, 7000 oak trees will be planted next to basalt columns, his contribution to documenta 7, curated by Rudi Fuchs.

“Imagine how many birds will flock to Kassel once these trees are here”, he says. “The planting of these 7000 trees is all about sculpture. It is the absence of originality. Once the tree has established itself, it’s just nature. A tree full of chirping birds with the wind blowing through it…music! This is sculpture that reaches far into the future. It will be a hundred years before tree and column have the right proportion to each other.”

Joseph Beuys, 7000 Eichen, documenta 7, Kassel, 1982, foto door Pieter Heijnen

Joseph Beuys, 7000 Eichen, documenta 7, Kassel, 1982

Joseph Beuys, 7000 Eichen, documenta 7, Kassel, 1982, foto Pieter Heijnen

Here, Joseph Beuys (Krefeld 1921 – Düsseldorf 1986) expresses in commonplace language his longing for art to be so much more than simply a colorful object that hangs on the wall or sits on the floor.

Art is a living bird, which lands on a living branch, of a living tree; or poops on the stone next to it. And he knows how to promote his work in a very practical way too; as when he strikes a deal with the manager of the local Holiday Inn. On the nightstands of all the hotel rooms, guests find a certificate to sponsor a tree.

As an artist and as a shaman, he works tirelessly to enable us to feel the essence of how magically interconnected the world is. Everything he creates is an expression of that inspiration. Once the oak is sufficiently big and strong, it’s roots will slowly topple the basalt column, producing an entirely new relationship between them. There is an obvious similarity here between the Old and New Testaments. In much of his work, either directly or indirectly, Beuys refers to the Christianity found in the Anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner.

In the 1930s he joins the Hitlerjugend and at the beginning of the Second World War Beuys volunteers for the Luftwaffe. He ends the war as an infanterist at the front of his hometown Cleve. Soon after his fighter-bomber crashes in 1943 in the Crimea, he is found by German reconnaissance. In 1964 however, in his self published artistic resume,

which is a declaration that for him there is no distinction between life and art, he transforms this accident into a miraculous rescue by nomads, who find him in the snow and keep him alive with fat and felt blankets. Experiences from the war and German guilt permeate his work.

As one of the first post-war western artists, Beuys is successful in communicating his all inclusive, holistic concept of art and bringing it to light. In doing so, he has even been known to prefer to communicate with dead animals rather than living people. In Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt from 1965 (How to Explain your Work to a Dead Hare), Beuys, as an initiated guide whose head is covered with honey and gold leaf, speaks about his drawings in a monologue to a dead hare, as he holds it lovingly in his lap. Under the little stool where they sit lies a bone with a piece of copper wire, as if it’s some kind of telephone that would connect you to an old, mysterious world. The public watches through a window, kept at bay. Modern art now has a Shaman in the house.

From the 1970’s on until his death, it’s impossible to imagine a major art manifestation anywhere in the world without the charismatic art and presence of Joseph Beuys. The public becomes familiar with his thousands of drawings, objects and installations. For me, an essential experience is when I hear his famous acoustic multiple Ja Ja Ja Ja Ja, Nee Nee Nee Nee Nee (1969), in which you hear him rhythmically repeat the words “ja” (yes) and “nee” (no). In spite of his slightly whiny voice, this is a surprisingly simple work of art with a very powerful message. Such an impressive way to express the concept of darkness and light.

RADICAL

When I ask myself now, in 2021, what the significance of Beuys and his work is for contemporary art, so much that had been pushed into the background comes back to mind. It is as if I have to adjust once again to the quiet warmth of his stacks of felt in the twilight of a basement. It is as if his dominant presence lies mysteriously dormant there, set aside, like potent seeds.

In his radical concept of art, everyone is an artist: not only the painter or sculptor, but also the parent, the nurse, the garbage collector. Whatever you do, if you do it with love and awareness, it is art. In this understanding of art, a society evolves wherein all people have the opportunity to feel good about the work they do and thus their life. For Beuys, there is no difference between art and politics either.

It is only natural that he becomes more and more involved in the political arena as an artist, aiming to reach as many participants as possible. With the founding of the Deutsche Stüdenten Partei (the German Student Party) in 1967, he proclaims, matter-of-factly, that most of the members are actually animals. Several years later, together with Johannes Stüttgen and Karl Fastabend, he opens, in an old shoe store in the center of Dusseldorf, the Organisation für Directe Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung (the Organisation for Direct Democratie via Referendum). He uses this political platform in 1972 at Documenta 5 to engage in a 100 day dialogue with the public. At the next Documenta in 1977, he presents the Free International University with a backdrop of his Hönigpumpe (honey pump) installation; symbolically representing a constant flow and exchange of ideas in society.

As one of the founders of the German political party, Die Grünen (the Green Party), he would like to run for the German Parliament. Even though Rosa Luxemburg’s quote “Freedom is always the freedom of the ones who think differently” hangs prominently on the wall of his studio, when it comes down to it, the party’s top decides not to take the risk. After all, what are they supposed to do with such a controversial and radical artist in parliament? For Beuys, a huge disappointment.

As one of the founders of the German political party, Die Grünen (the Green Party), he would like to run for the German Parliament. Even though Rosa Luxemburg's quote "Freedom is always the freedom of the ones who think differently" hangs prominently on the wall of his studio, when it comes down to it, the party's top decides not to take the risk

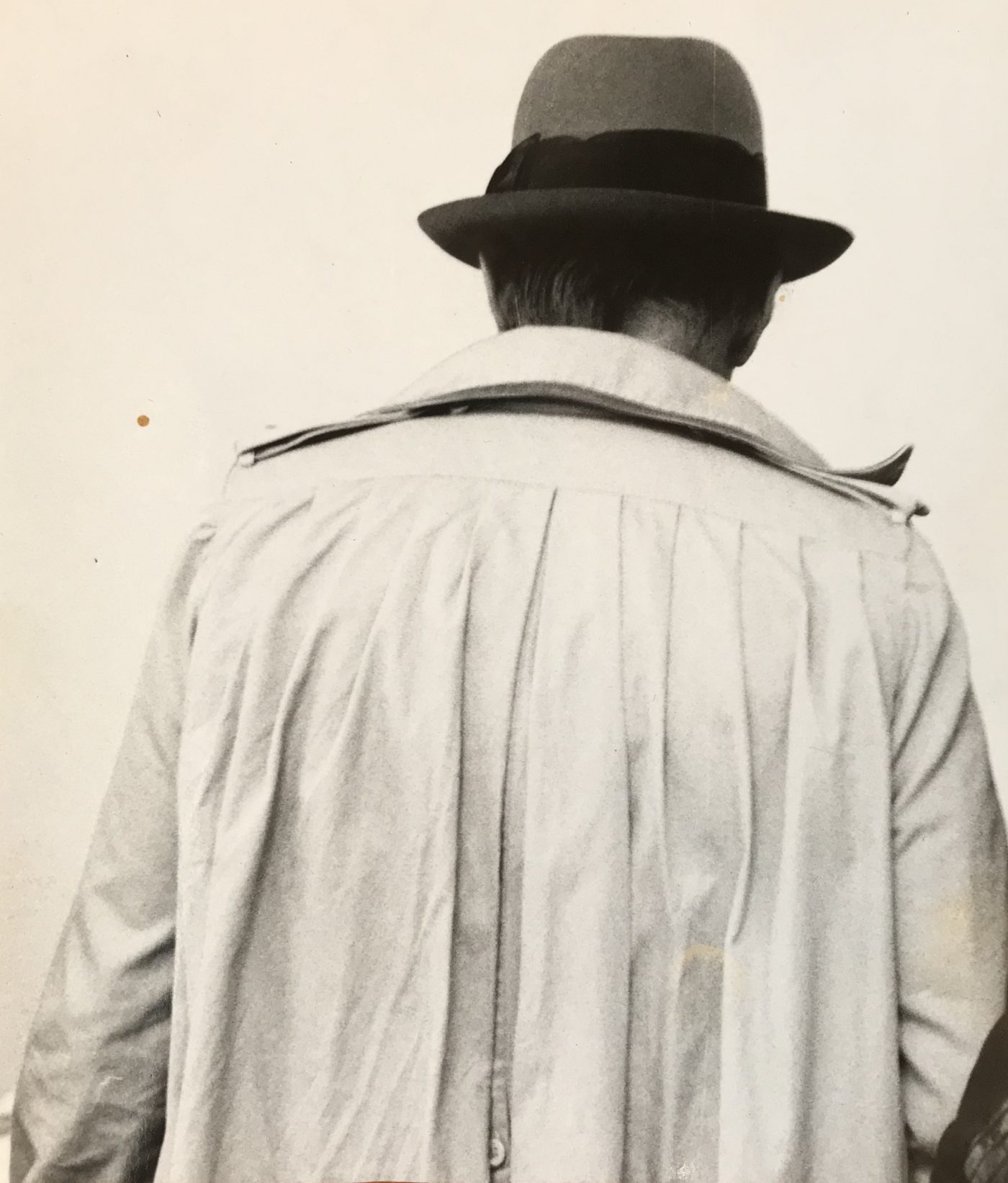

Joseph Beuys, atelier Düsseldorf, 1980, foto Pieter Heijnen

As we celebrate the one hundredth year of his birth, I think back to the autumn of 1969 when I first walk through the long hall into his class room at the Academy in Düsseldorf. It smells like fresh clay and a quilted cross with grips to hang on leans against the wall. It is pretty cool in there. As usual, Beuys arrives at school later in the day in his old, cobbled together Bentley. He spends a lot of time under the hood of that beast.

When I show him my portfolio, with little models for sculptures, he says, without skipping a beat, how nice this work would look on top of a piano. An almost deadly start, but I decide to stay a while longer. Long enough to realize that I will learn something here that will influence the direction of my life.

One summer evening he addresses a small group of students in front of the entrance to the stately academy building. He urges us to realize that the future of art lies outside the institution and in the open society. He holds his multiple Intuition (Intuition), 1968, up in the air. It is a little, modest, shallow pine box with two horizontal pencil lines drawn inside indicating the golden mean. He says that intuition is a higher form of thinking.

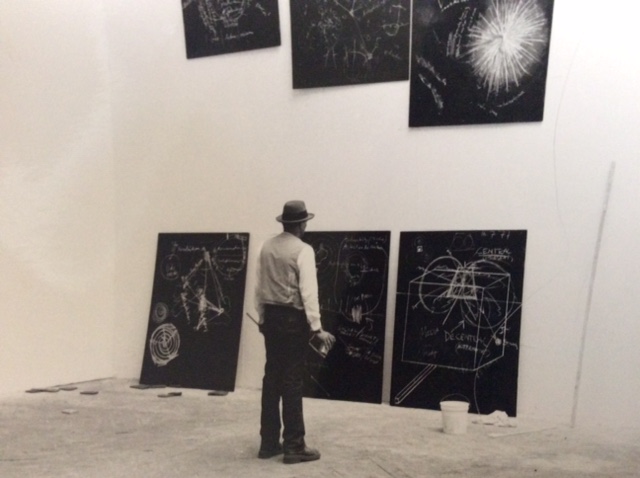

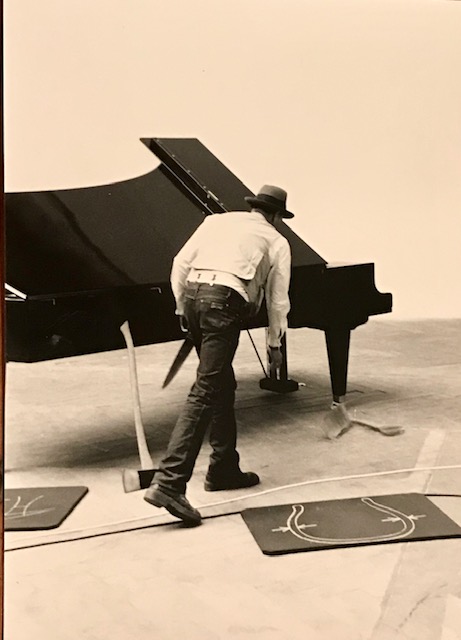

Joseph Beuys, Das Kapital Raum, Duits Paviljoen, 1980, foto Pieter Heijnen

Joseph Beuys, Das Kapital Raum, Biënnale van Venetië, 1980, foto Pieter Heijnen

BOIJMANS

After his dismissal from the Academy, Beuys ventures out into the whole wide world. He becomes famous as the man with the cane, fishing vest and his perpetual hat. Pressing forward, like a German infanterist, always headed to new projects.

I see him, in April 1980, invited by Wim Beeren to appear at the museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, in a public dialogue with experts from Rotterdam. In a packed gallery, he tirelessly explains his Plastische Theorie (theory of plastic arts): sculpture conceived of as an organic process, moving and constantly changing. On blackboards placed for his convenience, he draws the human figure with chalk. While he continues to elaborate, he creates lines representing streams of energy that move continuously from heart to feet and head. The constantly moving feet are warm and unformed while the thinking head becomes fixed in settled forms. Chalk in hand, he points to the drawing of the heart as he turns to the public and you hear him say in his resolute voice that the source of all love is right there.

Beuys does not erase his delicate drawings. As soon as he’s done with one, museum staff use fixative to preserve it, it is taken way and a new blackboard is placed in front of him for new figurations. Those blackboards are now part of his large installation Grond (Ground), 1980-81: consisting of copper plates mounted in open wooden crates that look like big batteries. Periodically you hear his listless voice coming from a speaker Und jetzt brechen wir den Scheiss hier ab (And now, let’s cut this bullshit).

Beuys is uniquely able to invoke the complementary forces of birth, death and reincarnation with humble materials, such as in the installation Zeige deine Wünde (Show your wound), 1974-75. As I witness the presentation of this major work on a wintry day at the Lenbachhaus in Munich, I experience the deep mistrust and defiance his work provokes. While inside, at the head of a long table, Beuys raises his glass with a Prost Herr Marx (cheers, Mr. Marx), toasting the collector who will donate this piece to the museum, I hear and see a charged crowd screaming “Beuys raus, Beuys raus” (Beuys out, Beuys out) outside in the snow. His art has touched a raw nerve here.

Entartete Kunst (degenerate art). Under a thin, shiny surface, the memory of pitch black nazi times is palpable. Not only there and then, but now, everywhere, right in your face, inescapable and in broad daylight. Beuys’ Germany is complicated.

He celebrates his 59th birthday in a nice, new house, where, in the hall next to the new beautiful bathroom, his larger than life portrait leans against the wall. Andy Warhol made it. There is a rumor they will collaborate on something. In the middle of the festivities, a taxi stops at the door. The artist, A.R. Penck steps out. Straight from his mother’s house in Dresden, thrown out of the country; expatriated. Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik walk towards him with open arms.

With his retrospective show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in the winter of 1979-80, Beuys is introduced to a wider, American public. He makes a profound impression. His large sculpture Tallow (fat), 1977, is made of five big blocks of solid animal fat (besides copper and felt, fat is a staple of Beuys’ artistic vocabulary). It’s temperature is painstakingly monitored as the form of the sculpture would literally change if the piece would get too warm and the fat would melt.

In the international art center of the world at the time, Beuys seems to turn the prevailing, comfortable formalism of the latter years of modernism upside down with simple thermometers. Suddenly, modernism and its American legacy have to deal with the holistic, contemporary art of Joseph Beuys, that emerges from personal mythologies born from a dark, complex daily life. Expansive artistic declarations juxtaposed to the impersonal emptiness in the boxes by Donald Judd.

Joseph Beuys, Das Kapital Raum, Biënnale van Venetië, 1980, foto Pieter Heijnen

Joseph Beuys, Das Kapital Raum, Biënnale van Venetië, 1980, foto Pieter Heijnen

Leading critics oppose him and Beuys gradually falls victim to a malicious cancel culture. Since in Beuys’ work, what you see is far from everything there, these critics find no room for his work in the canon of modernism.

And yet, I see a lot of kinship to a social commitment in contemporary art. Perhaps, some day, one will be able to not only purchase Picasso ceramics in museum shops, but also Beuys thermometers.

In a dream, I sit at the kitchen table of a little farm house that was built on an ancient riverbed, and all of a sudden Joseph Beuys steps out of the wall for a short visit. The house is surrounded by many trees, planted by birds, squirrels and the wind. I feel very much at home.

After his death it has become increasingly quiet. Much of the mystery and magic that animated his work has faded into the background. What remains are the drawings, the objects, the concepts.

Alas, the shaman is dead.

‘En als de boom groot is, is de planter allang dood.’ Hij zegt het lachend als hij in april 1982 in Kassel met een aantal medewerkers gaten in de aarde graaft voor zijn grootschalige kunstwerk 7000 eiken. Over het hele stadsgebied zullen duizenden jonge bomen worden geplant, naast basalten zuiltjes. Het is zijn bijdrage aan documenta 7, waarvan Rudi Fuchs de algehele leiding heeft.

‘Stel je eens voor hoeveel vogels er naar Kassel zullen komen als die bomen hier staan’, zegt hij. ‘Het planten van die zevenduizend eiken heeft alles met beeldhouwkunst te maken. Het is afzien van originaliteit. Als de boom er eenmaal staat is het gewoon natuur geworden. Een boom met kwetterende vogels en de wind die er doorheen blaast… Muziek! Dit is een sculptuur die heel ver in de toekomst reikt. Pas na zo’n honderd jaar staan eik en zuil in een juiste verhouding tot elkaar.’

Joseph Beuys (Krefeld, 1921-Düsseldorf, 1986) geeft hier in alledaagse spreektaal blijk van zijn verlangen dat kunst veel meer kan zijn dan een kleurig object aan de muur of op de vloer van een of ander museum. Kunst is een levende vogel die op een levende tak van een levende boom landt, of op de steen ernaast poept. Hij brengt zijn werk ook heel praktisch aan de man. Zo heeft hij in Kassel een deal gemaakt met de directeur van de plaatselijke Holiday Inn. Op de nachtkastjes van alle hotelkamers zullen de gasten certificaten vinden waarmee ze een boom kunnen sponsoren.

Als kunstenaar en sjamaan doet hij er alles aan om ons te laten voelen hoe magisch de samenhang in de wereld in wezen is. Alles wat uit zijn handen komt is een uitdrukking van die bezieling. Als de eik groot en sterk genoeg is, zullen zijn wortels het basalten zuiltje langzaam omver drukken, waardoor er een nieuwe verhouding ontstaat tussen boom en zuil. Een bijbelse vergelijking met het Oude en Nieuwe Testament ligt hier voor de hand. In heel veel werk grijpt hij direct en indirect terug op de christelijke traditie die Rudolf Steiner in zijn antroposofie heeft verweven.

Als een van de eersten in de naoorlogse westerse kunst weet Beuys zijn alomvattende holistische kunstopvatting succesvol voor het voetlicht te brengen. Soms communiceert hij daarbij liever met dode dieren dan met levende mensen. In Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt (‘Hoe je aan een dode haas schilderijen uitlegt’) uit 1965 voert Beuys, wiens hoofd bedekt is met honing en bladgoud, als een ingewijde gids, een monoloog over zijn tekeningen met een levenloze haas, die hij liefdevol op zijn schoot koestert. Onder het krukje waarop hij zit, ligt een bot met een stukje koperdraad, als was het een telefoon waarmee je toegang krijgt tot een oude, mysterieuze wereld. Het publiek kijkt door een raam op afstand toe. Het is duidelijk dat de moderne kunst dan ook een sjamaan in huis heeft.

Vanaf de jaren zeventig tot aan zijn dood is zijn werk en de charismatische persoon van Beuys niet weg te denken uit alle megakunstmanifestaties, die dan allengs wereldwijd worden georganiseerd. Het publiek raakt vertrouwd met zijn duizenden tekeningen, objecten en installaties. Voor mij gaat het licht aan bij het horen van zijn beroemde akoestische multiple Ja Ja Ja Ja Ja, Nee Nee Nee Nee Nee (1969), waarin hij enkel de woorden ‘ja’ en ‘nee’ uitspreekt. Zelfs als zijn stem wat zeurderig klinkt, blijft het een overrompelend eenvoudig kunstwerk met enorme zeggingskracht. Wat een vondst om het concept van licht en donker zo voor te stellen!

Radicaal

Als ik me in 2021 afvraag wat Beuys en zijn werk betekenen voor de hedendaagse kunst, dan komt er heel wat naar boven dat in de loop der jaren naar de achtergrond is gedrongen. Het is alsof ik in het halfdonker van een kelderruimte opnieuw moet wennen aan de stille warmte in zijn stapels vilt. Alsof zijn dominante aanwezigheid verdrongen is door een mysterieuze onzichtbaarheid die daar in het halfdonker als kiemkrachtig zaad ligt opgeslagen.

In zijn radicale opvatting van kunst is ieder mens een kunstenaar: niet alleen de schilder of beeldhouwer, maar ook de ouder, ziekenverzorger of vuilnisman. Wat je ook doet, als je het met liefde en volle aandacht doet dan is het kunst en in die kunstvorm ontplooit zich een samenleving waarin mensen van allerlei slag de gelegenheid krijgen om iets goeds van hun leven te maken. Voor hem is er geen onderscheid tussen kunst en politiek.

Het is bijna vanzelfsprekend dat hij zich als kunstenaar steeds meer in de politieke arena begeeft, waarbij hij ernaar streeft om zoveel mogelijk deelnemers te bereiken. Bij de oprichting van de Deutsche Studenten Partei in 1967, verklaart hij laconiek dat de meeste leden dieren zijn. Enkele jaren later opent hij, samen met Johannes Stüttgen en Karl Fastabend, in de binnenstad van Düsseldorf in een oude schoenenwinkel Organisation für Direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung, een politiek platform waarmee hij in 1972 op documenta 5 gedurende honderd dagen met publiek discussieert. Op de volgende documenta in 1977 presenteert hij de Free International University tegen de achtergrond van zijn Honingpomp-installatie, die als een symbolische bloedsomloop de constante stroom en uitwisseling van ideeën in de samenleving weergeeft.

Als een van de oprichters van de Duitse politieke partij Die Grünen wil hij zich in 1979 kandidaat stellen voor de Bondsdag. Weliswaar heeft hij het citaat ‘Freiheit ist immer die Freiheit der Andersdenkenden’ (‘Vrijheid is altijd de vrijheid van andersdenkenden’) van de revolutionaire Rosa Luxemburg aan de muur van zijn atelier hangen, maar als het erop aankomt houdt het partijbestuur de boot af. Wat moet je met zo’n omstreden, radicale kunstenaar in het parlement? Het is een grote teleurstelling.

Bij de viering van zijn honderdste geboortejaar denk ik terug aan de herfst van 1969 als ik voor het eerst via de lange gang zijn klas in de academie van Düsseldorf binnenwandel. Het ruikt er naar verse klei en er staat een gewatteerd kruis tegen de muur met handvaten waar je aan kan gaan hangen. Het is er koel. Beuys komt, als altijd, later die dag naar school in zijn oude, opgelapte Bentley. Hij brengt veel tijd door onder de motorkap van dat beest.

Als ik hem mijn map laat zien met modelletjes voor sculpturen, zegt hij zonder aarzelen dat dit werk heel mooi op een piano zal staan. Een bijna dodelijk begin, maar ik blijf nog even. Lang genoeg om me te realiseren dat ik hier iets over kunst kan leren dat mijn leven richting geeft.

Op een zomeravond spreekt hij voor de ingang van het imposante academiegebouw een groepje studenten toe. Hij drukt ons op het hart dat de toekomst van de kunst buiten het instituut in de open samenleving ligt en houdt zijn multiple Intuition (1968) in de lucht. Het is een bescheiden, ondiep, vurenhouten kistje waarin twee horizontale potloodlijnen zich in een gulden snede tot elkaar verhouden. Hij zegt dat intuïtie een hogere vorm van denken is.

Boijmans

Na zijn ontslag aan de academie trekt Beuys zelf de wijde wereld in. Hij wordt beroemd als de man met de wandelstok, het vissersvest en de onafscheidelijke hoed. Met de gang van een Duitse infanterist is hij altijd onderweg naar nieuwe projecten.

In april 1980 zie ik hem op uitnodiging van Wim Beeren in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in publieke discussies en in gesprek met specialisten uit de Rotterdamse samenleving. Onvermoeibaar geeft hij daar in een volgepakte museumzaal uitleg over zijn ‘plastische theorie’: beeldhouwkunst opgevat als een organisch proces dat voortdurend beweegt en verandert. Op schoolborden die voor hem zijn klaargezet, tekent hij met krijt een mensenfiguur. Hij praat maar door en formuleert met lijnen een energiestroom die zich vanuit het hart tussen voeten en hoofd voltrekt. De immer onderweg zijnde voeten zijn warm en ongevormd, terwijl het denkende hoofd verstart in vaste vormen. Met het krijtje in zijn hand wijst hij naar het getekende hart en terwijl hij zich omkeert naar het publiek hoor je hem met zijn vastberaden stem verklaren dat dat de bron van alle liefde is.

Beuys veegt zijn tere krijttekeningen niet uit. Zodra er een af is, wordt de tekening door museummensen gefixeerd en komt er een schoon bord om nieuwe figuraties te ontvangen. Die schoolborden vormen nu een geheel met zijn grote installatie Grond (1980-81): koperen platen gevat in open kisten van hout die ogen als grote accu’s. Af en toe hoor je uit een luidspreker zijn vermoeide stem ‘Und jetzt brechen wir den Scheiss hier ab’ (‘En nu breken we de zooi hier af’).

Met karige middelen weet Beuys de complementaire krachten van leven, dood en wedergeboorte onnavolgbaar vast te leggen, zoals in zijn ruimtelijk werk Zeige deine Wunde (1974-75). Als deze indringende installatie in een winters München in het Lenbachhaus wordt gepresenteerd, ervaar ik het diepe wantrouwen en de weerstand die hij oproept. Terwijl Beuys binnen aan het hoofd van een lange tafel met de woorden ‘Prost Herr Marx’ zijn glas heft, om de verzamelaar te bedanken die dit werk aan het museum zal schenken, zie en hoor ik buiten in de sneeuw een opgewonden menigte ‘Beuys raus, Beuys raus’ joelen. Hier raakt zijn kunst een rauwe zenuw. ‘Entartete Kunst’. Onder een dun, glanzend bovenlaagje ligt de herinnering aan de gitzwarte nazitijd zo voor het grijpen. Niet alleen hier en toen, maar ook nu overal, recht in je gezicht, onontkoombaar en op klaarlichte dag. Het Duitsland van Beuys is complex.

Hij viert zijn zestigste verjaardag in een mooi nieuw huis, waar in de gang, naast de fraaie badkamer, zijn meer dan levensgrote portret tegen de muur leunt. Andy Warhol heeft het gemaakt. Men mompelt dat ze samen iets zullen gaan doen. Er stopt een taxi in het feestgedruis. De kunstenaar A.R. Penck stapt uit. Zo vanuit het huis van zijn moeder in Dresden, hij was net het land uitgegooid: Ausgebürgert. Joseph Beuys en Nam June Paik lopen met open armen naar hem toe.

Zijn overzichtstentoonstelling in het Guggenheim Museum in New York, in de winter van 1979-80, introduceert Beuys bij het grotere Amerikaans publiek. Hij maakt indruk. De temperatuur van zijn enorme sculptuur Tallow (1977) die uit vijf grote blokken gestold dierlijk vet bestaat (naast koper en vilt is vet een van de herkenbare materialen uit zijn artistieke vocabulaire), wordt nauwkeurig gemeten, omdat het werk letterlijk van vorm verandert als het vet te warm wordt en gaat smelten.

In het toenmalige internationale kunstcentrum van de wereld lijkt Beuys het overheersende, comfortabele formalisme in de nadagen van het modernisme volledig op zijn kop te zetten met thermometers. Plotseling heeft het modernisme en zijn Amerikaanse erfenis te maken met de holistische, eigentijdse kunst van Joseph Beuys, waarin persoonlijke mythologieën uit een duister en complex dagelijks leven de boventoon voeren. Expansieve aanspraken van kunst tegenover de onmenselijke leegte in een doos van Donald Judd.

Toonaangevende critici verzetten zich en van lieverlede valt Beuys ten prooi aan een kwaadaardige zwijgcultuur. Omdat in Beuys’ werk lang niet alles is wat je ziet, past zijn werk, wat de critici betreft, niet in de canon van het modernisme.

Toch komt de maatschappelijke betrokkenheid in veel eigentijdse kunst me heel bekend voor. Ik zie verwantschap. En wellicht kun je binnenkort in museumwinkels naast Picasso-keramiek ook Beuys-thermometers kopen.

In een droom zit ik aan de keukentafel van een boerenhuisje, dat op een oude rivierbedding is gebouwd en ineens stapt Joseph Beuys door de muur naar binnen voor een kort bezoek. Rondom het huis staan veel bomen die daar door vogels, eekhoorns en de wind zijn geplant. Ik voel me er thuis.

Na zijn dood is het allengs stiller geworden. Veel van het mysterie en de magie waarmee hij zijn werk bezielde is naar de achtergrond gedrongen. Wat overblijft zijn de tekeningen, objecten en concepten.

Helaas is de sjamaan dood.

Everyone is an Artist: Cosmopolitan Exercises with Joseph Beuys – K20, Dusseldorf – 27.3 through 15.8.2021

Matare + Beuys + Immendorff – Akademie-Galerie, Dusseldorf – 27.3 through 20.6.2021

The Catalyst – Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen – 28.3. through 8.8.2021

Joseph Beuys, Perpetual Motion – Skulpturenpark Waldfrieden, Wuppertal – 28.3 through 20.6.2021

Pieter Heijnen

is beeldend kunstenaar