Performing Colonial Toxicity – A conversation with Samia Henni

Each bomb tells its own story. Talking to Samia Henni about her extensive research of seventeen nuclear bombs detonated by the French government in the Algerian Sahara, irrevocably effecting the environment and the lives of the people living and working there. It was subject of a show at Framer Framed and now also of a book that has been presented by Framer Framed and If I Can’t Dance this weekend.

Between 1960 and 1966 the French government detonated seventeen nuclear bombs in the Algerian Sahara, irrevocably effecting the environment and the lives of the people living and working there – a secret mission that has swiftly been swept under the carpet. This is the final weekend that researcher and architectural historian Samia Henni presents her extensive research on French nuclear colonialism at Framer Framed in Amsterdam.

Based on extensive and collective research into the traumatic and unresolved nuclear history between France and Algeria, Samia Henni has compiled a public archive containing classified confidential materials on the French government’s nuclear program conducted in the Algerian Sahara between 1960 and 1966. During this secret nuclear operation, seventeen bombs were detonated, leaving destructive and irreparable traces on the lives and health conditions of the Sahara’s residents, veterans involved in the nuclear program, victims of these operations, and the overall natural environment of the region and beyond.

After visiting the exhibition several times, I arranged a conversation with Samia Henni via Zoom to talk about some exhibition aspects that to my opinion need more attention and reflection. The exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity was developed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution and curated by Megan Hoetger..‘The exhibition is not really about art’, Henni explains. ‘Rather, it’s about communicating the histories of the events between 1960 and 1966, and what happened after 1966 until today. The exhibition delves into events that shape various aspects of life, such as the production and circulation of radioactivity, embedded violence, and confined spaces and remaining architectural structures associated with the French nuclear program. These narratives, which are often overlooked and under-researched, find a unique platform in exhibitions. In exhibitions, visuals and materials coalesce, engaging in a dialogue that transcends the linear structure of written text.’

Performing Colonial Toxicity indeed takes on a particular format which could be considered the result of a process of collective archiving, an approach that Henni has established over the course of her artistic practice. In the past few years, she has presented multiple historical exhibitions based on archival materials, in which she developed a method of translating text – the predominant form of documenting and transmitting information – into comprehensible exhibition formats that explore specific historical contexts. Simultaneously, these exhibitions function as historical archives and as a juxtaposition of different textual, audio, video and sound narratives. As a researcher and an academic, Henni naturally working with textual sources and produces texts herself. However, developing exhibitions enables her to bypass the limitations of traditional book formats and present archival information in radically different configurations.

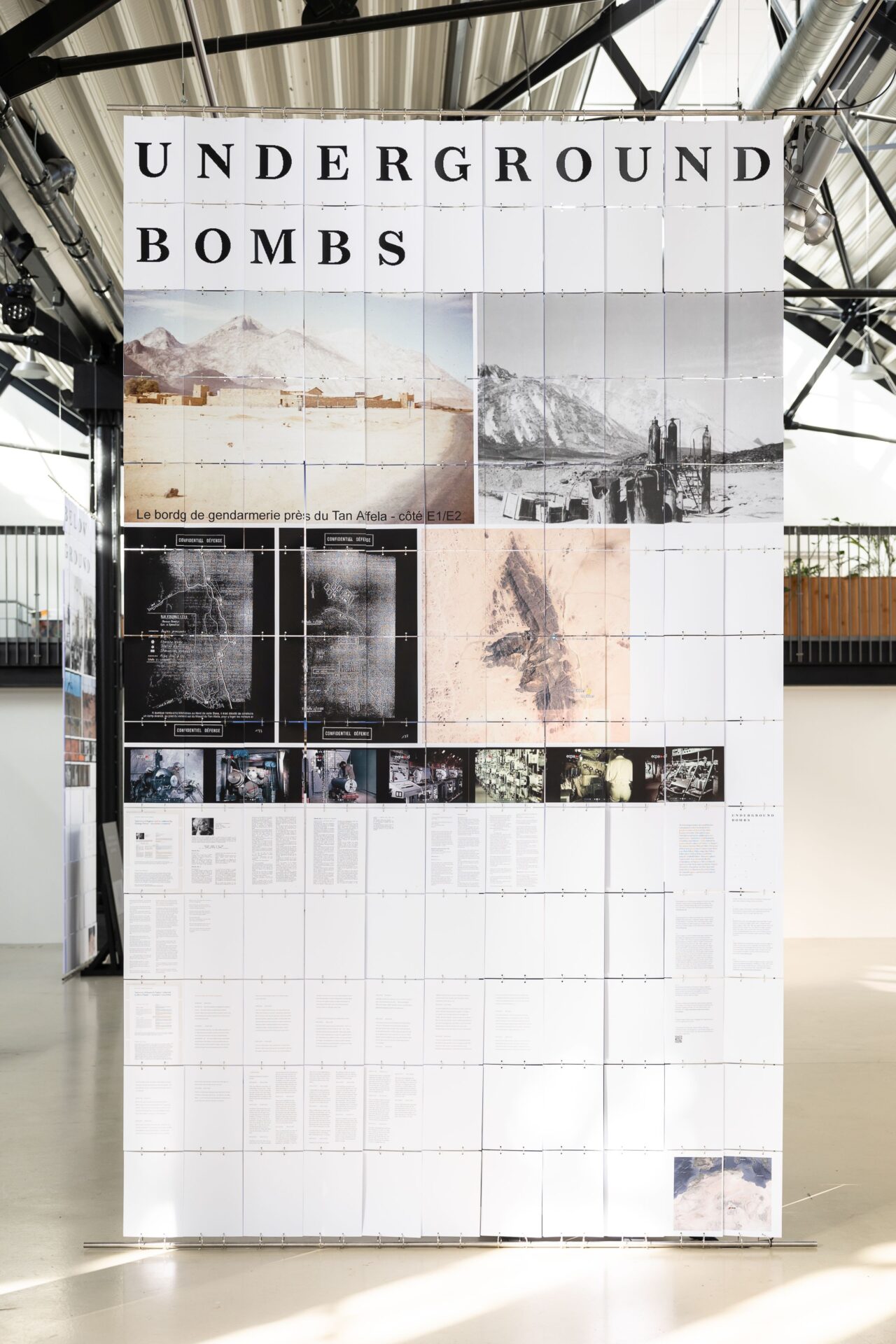

In Performing Colonial Toxicity collected research material is thematically organized into thirteen stations with information printed on a hanging from the ceiling paper canvas which are composed of A4 paper sheets connected by metal rings. Each station combines illustrations, photos, text of different sizes and nature, video projections, some stations are accompanied by plasma screens with documentation of interviews which Henni conducted with researchers and physics, environmental activists and Sakhara residents, among video material are also footage of documentary makers and artists. The stations include such headings like: Justes, Atmospheric Bombs, Underground Bombs, Below Ground, Exposure, Survivors, Beryl Bomb, Jerboasite, Tan Affela, Reggane Base, etc. Via qr codes it is possible to get into the texts and audio files with testimonies of the nuclear program victims.

The exhibition serves as an associative case studies of enduring violence, legitimized by both the French and Algerian governments. As a whole, the exhibition manifests the consequences of Europe’s colonial past and the irreversible environmental damages caused by the execution of French nuclear power on living bodies and the natural landscape of the Algerian Sahara. This research project has been thoroughly documented and mediated by Framer Framed, If I Can’t Dance, and Henni herself. Aside from the physical exhibition, the project includes a podcast episode and several performance lectures. After the conclusion of the physical exhibition, the presented research materials will still be accessible on the online platform The Testimony Translation Project. Hosted on the If I Can’t Dance website, the platform features forty written and oral testimonies from French and Algerian victims of the nuclear program, translated and published for the first time. Additionally, Henni’s upcoming book, Colonial Toxicity: Rehearsing French Radioactive Architecture and Landscape in the Sahara (2024), a comprehensive volume presenting the research materials in full detail, will be presented at the finissage of the exhibition on 14 January.

The exhibition Performing Colonial Toxicity opened in October 2023, in a time when the world’s nuclear powers are again threatening the global population. Over the last two years, since the beginning of Russia’s War on Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has consistently proclaimed nuclear threats using various wordings on different occasions. This, of course, triggers fears and unrest inherited from the Cold War times. The presence of the atomic memory has been embedded in the global political DNA since the invention and detonation of the first atomic bombs 1945. Since then, visual mass culture has been inspired by the plot over and over again, as testified in films such as the recent Oppenheimer (2023, directed and written by Christopher Nolan) and earlier by the autobiographical Soviet film Take Aim (1974, directed by Igor Talankin). Both films unfold around the personal dilemmas facing the scientists who worked on the atomic weapons: Robert Oppenheimer and Igor Kurchatov, a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons.

Intersecting in this timely yet ever-relevant framework, Henni’s research project contributes largely to the knowledge about the history of European nuclear power, in which France plays a crucial role as an ambitious state that invested largely into its nuclear program – apparently without taking account of its consequences and damages.

In 2017 Henni presented a similar project, the exhibition Discreet Violence: Architecture and the French War in Algeria at Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, in which she investigated the spatial operations that the French army and colonial administration enforced in colonized Algeria during the Algerian Revolution (1954–1962). The exhibition consisted of texts, maps, photographs, films, and voices distributed across thirteen exhibit cases, nine flat screens, and three headsets, all of which were surrounded by a wallpaper of newspaper articles.

With Performing Colonial Toxicity, also organised into thirteen thematic stations, Henni continues to create tangible, sensual, layered and movable narratives that aim to bring into the public spotlight a chapter of French – Algerian political and environmental history. By designing her material in a layered, multidimensional and multiscaled manner, Henni aims to activate the physical and emotional potentialities of the exhibition visitors in grasping complex historical narratives. The foldable format of her exhibitions also allows them to be transported easily as a flatpack, to be unfolded in different locations. Discreet Violence, for instance, travelled to seven institutions across three continents over a period of two years. Hopefully, Performing Colonial Toxicity will have a similar showcasing intensity and wide geographical scope.

The exhibition as a form of writing

One of the main strands I wanted to develop during our conversation is a notion of the exhibition as a form of writing, which Henni wrote about earlier . I ask Samia to elaborate on this notion in relation to Performing Colonial Toxicity and possibly draw some parallels and differences between texts and exhibitions. She answers: ‘In the exhibition format an exceptional aspect lies in the ability to showcase diverse visual materials that speak to each other. The non-linear arrangement allows visitors to navigate freely, moving between stations like fragments of a larger narrative.’ The comprehensive picture of the exhibition emerges when all these fragments are considered together, yet it’s not obligatory for viewers to engage with the entire display, Henni explains. ‘While text is linear and therefore dictates how you should navigate and understand these histories, exhibitions are more open systems. They present very different possibilities than a song or a poem, it’s more like an event that unfolds in front of us and we have to try to understand how to read it. I don’t expect that visitors will read each text in the exhibition the same way. They’re all very, very different.

Exhibitions can take on a more associative form, allowing narratives to speak to each other, acknowledging contradictions and presenting opposing perspectives side by side. This method becomes crucial, especially when dealing with classified archives that limit access to institutional narratives. The initial step involves gathering as much information as possible, organising it through a narrative that extends beyond the text – encompassing voices, stories, and a unique way of narrating events. The challenge lies in the varied interpretations visitors might have, given the complexity of the subject matter. To facilitate understanding, I include texts at each station, providing references for those seeking deeper insight. The goal is to provoke curiosity and to allow visitors to engage with the content at their own pace.

The interviews scattered throughout the space, presented as massive text headings are visible from a distance, add another layer to the exhibition. There are also video screens, interspersed with the text on paper, in which people are interviewed. These videos are presented without sound, encouraging viewers to create their own internal dialogue while witnessing the visual elements. The intentional relationships, juxtapositions, and links within the exhibition may be planned by me as an exhibition maker, but they remain somewhat hidden from the audience, allowing for a more organic and individual viewer experience.

The inclusion of sound functions to further transform the visitor’s engagement, contributing to a distinct bodily response. The physicality of being present in the exhibition space, confronted with unfamiliar images, also enhances the sensory experience, allowing for a more profound connection.’

How to Perform What is Not There?

Upon engaging in discussions with Henni and meticulously studying materials published around the project I have come across different approaches towards ‘performing’ and ‘performativity’ within Performing Colonial Toxicity that I’d like to address. If I Can Dance is an art organization with an explicit mandate to broaden the conceptual boundaries of performativity and apply the act of performance across diverse contexts. Within Performing Colonial Toxicity the prevalence of performativity and theatrical terminology is evident. In the exhibition handout , the term is expanded on, describing the project as a ‘public stage’ and ‘engaging the audience in the act of “performing” and encouraging the entire body of visitors to participate in the act of reading.’ This is intended to involve the potential for a ‘social performance’ and serve as ’a reminder of the political force of performative speech acts’.

In my estimation, such an inclination seems quite excessive and imposed within the context of a project whose principal objective is the dissemination of archival documents and historical evidence to the public to establish social and environmental justice. Presented in the art venue of Framer Framed in a format of a pop-up public library on European nuclear history, Performing Colonial Toxicity is gaining its wider presence within the public domain without an ambition to transform from a public archive into an art project or a series of performative acts. The broad and frequent use of ‘performativity’ within the project raises concerns about potential misinterpretation. Within the artistic domain, the term risks diminishing the historical gravity, political and ecological seriousness and the impact of the events addressed by Samia Henni in her research. This seems to be a case when art, driven by goodwill, has a potential to cause harm. Possibly, in the case of the presentation of archival evidence and personal testimonies of very concrete individuals within the Performing Colonial Toxicity, no abstraction is needed since historical facts and tragic life stories speak for themselves.

Therefore, clarification may be needed regarding the specific meaning of “performing” in relation to this research and its public presentation. Henni explains its meaning in the project: ‘The central concept of the exhibition is to explore how to make colonial toxicity perform. The objective is to understand how the toxicity evident in all presented forms – whether visual evidence, texts, witness testimonies, maps, stills, or sound – can actively manifest in the exhibition space. For Henni, it is crucial that the exhibition is not static but rather something tangible that touches, disrupts, disturbs, and affects the bodies of the visitors. In this context, ‘to perform’ means being present in the space, carrying out actions, having a temporal and spatial impact, and creating a dynamic experience. The notion of performing is not about staging a performance; it is an ongoing action verb. The idea is that upon entering the space, colonial toxicity must perform, generating effects and leaving traces. It is through our bodies that we can comprehend the multifaceted and invisible effects of radioactivity and toxicity, effects that endure indefinitely and are irreversible.’

All images: Installation photos of the exhibition ‘Performing Colonial Toxicity’ (2023) by Samia Henni at Framer Framed in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. Foto: © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

Final Weekend Performing Colonial Toxicity! Events: January 13th: Screening: And still, it remains. Within the frame of the exhibition, the new artists’ film And still, it remains by directing duo Arwa Aburawa and Turab Shah is presented. On January 14th Book Presentation. Colonial Toxicity: Rehearsing French Radioactive Architecture and Landscape in the Sahara (2024) a new publication by Samia Henni. This publication brings together nearly six hundred pages of materials documenting this violent history of France’s nuclear bomb programme in the Algerian desert. Meticulously culled together by the architectural historian from across available, offered, contraband, and leaked sources, the book is a rich repository for all those concerned with histories of nuclear weapons and engaged at the intersections of spatial, social and environmental justice, as well as anticolonial archival practices.

Author: Samia Henni

Managing editor: Megan Hoetger

Contributing editor: Georg Rutishauser

Copy editor: Janine Armin

Design: François Girard-Meunier

Publishers:

Framer Framed,

If I Can’t Dance,

edition fink.

Notes

[1] Exhibition as a Form of Writing. On “Discreet Violence: Architecture of the French War in Algeria”, Samia Hennl, Parse Journal (2021) https://parsejournal.com/article/exhibition-as-a-form-of-writing/

[2] Performing Colonial Toxicity. Exhibition Handout. Curatorial Note by Megan Hoetger, p.9-13. Link: https://framerframed.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/web_EN_Performing-Colonial-Toxicity.pdf

Anna Bitkina

is a curator of contemporary art, performative projects and educational programs, she is a co-founder of a nomadic curatorial collective TOK