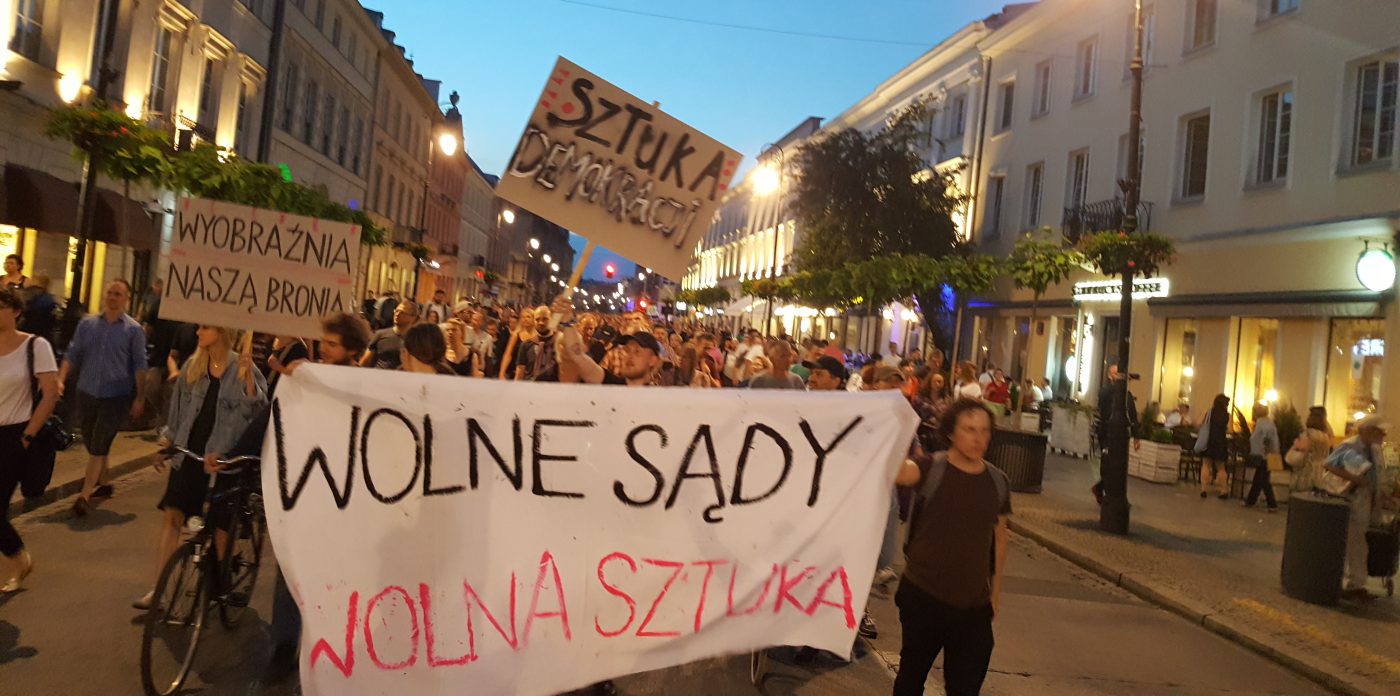

Demonstrations in July 2017, with slogans “imagination our weapon”, “free art free judgements (courts)” “the art of democracy”.

In Poland, which is to say everywhere

What to do against the upcoming fascism around us? Kuba Szreder, a Polish writer and curator, sees a few openings in the dark.

Shrit happens. It happened in Poland. It happened in the United States, Hungary, Turkey, Austria, India, Finland, Israel, Syria, in little Britain as well. It could have happened in The Netherlands or France too. Or in Germany, yet again. Recently, a Dutch friend, a politically engaged artist, asked me: how can we show solidarity with our Polish comrades? How can we be of help? I stuttered a bit, not knowing what to say, tried to explain nuances without losing a bigger picture, in an upbeat tone, but not diminishing the gravity of our current predicaments. Playing a victim and pity-mongering would be an easy thing to do. We poor folks somewhere at the verge of civilized world, coping with our demons, not being European, democratic, modern enough. Please, help us. Well, but maybe it is all the other way around. What happens in Poland is actually a symptom of integrating into a well-established European family, catching up with Western modernity, a glorious history of warring national states, genocide, colonialism and fascism.

Considering the global spread of this shrit, the question should be rephrased accordingly: how do we help each other to get out of it? Possibly nobody has a good answer, but how could we have one, if the only ones that matter will be recognized years after they proved their merit. Just as my friend meant it, such a question is an expression of solidarity, evocation of shared understanding that we are all in this shrit together.

For years, people of the left have actually warned that a shrit storm is coming. The history proved these warnings not to be fear-mongering, as the liberal commentariat loved to mock them, but a sound and solid analysis. Immanuel Wallerstein and others explained clearly that ours are the times of interregnum and turmoil, capitalism as we know it waning, a new system not yet born, and without any guarantee that what comes next will be any better. Taking a brief look at the presidential face of the most powerful country of the ancient regime, actually makes one wonder.

But back to Poland. Neo-authoritarianism, taking a good lesson from Carl Schmitt, indulges in creating divisions, because that is the only way they are able to legitimize their power grabs and the ascent of myriads of Ubu Kings to their sinecures. There are two enemies: internal and external. Both are barely existing, but it does not matter. The role of the external one is played by Islamists. Actually, the real difference between Poland and Western Europe is a miniscule presence of Muslim communities, and the ones that are around are peaceful, well-integrated folks (just as it happens everywhere anyway). And yet, Poland is a vehemently anti-migrant (anti-Muslim) country. The less people are exposed to otherness, the more they are afraid of it. When people of the Left were turning Facebook into a tool for mass mobilization (or indulging in cosy, lefty echo chambers), the neo-authoritarians weaponized it into a tool of mass politics. Just as tsarist secret police did in late nineteenth century, writing infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which incited antisemitism and pogroms, the alt-right stirs up hatred in the media landscape constituted by multitudes of global villages. Religion and nations are powerful, unifying narratives in this scattered landscape, empty signifiers, vague enough to be manipulated at will, but powerful too, idols and sources of legitimization in their own right. And here comes a challenge to engaged artists and other comrades: how to puncture these echo chambers, provide other unifying narratives, while the ones we cherish have a rather modest pull and do not stir up emotions beyond lecture halls or niche journals.

It is especially problematic due to the political construct of the internal enemy. In Poland, which is to say everywhere, it has the face of a lefty liberal, a figure well-known from the American culture wars, frequenting pages of a yellow press worldwide, meaning usually a self-satisfied member of globalized elite, separated from lives and concerns of ‘normal’ people. Obviously, this stereotype is peddled by right wing journalists, PR specialists and politicians, well-paid and not any less elitist. In fact, much more detached from the everyday concerns of multitudes than pauperized artistic or intellectual workforce actually is. Surprised, people of the left found themselves in the same group with neoliberals, who – when they still had the power to do so – forcefully eradicated any presence of left thinking from public discourse, getting us into this shrit in the first place. But willingly or not, people of the left find themselves on the same side of the political divide with neoliberals, when it comes to defending whatever is left of democratic mechanisms. Popular front? Sounds good, but… Pro-democratic demonstrations in our Ubucountry tend to be rather ironic affairs. The stage is usually occupied by ‘leaders of pro-democratic forces’, frequently neoliberals in anything but the name, who condemn neo-authoritarians as neo-communists (a synonym of totalitarianism), while the latter smear liberals as detached lefties, who defend nothing but their own privilege. The real left, including artists, stand in the middle of this shouting match, stunned and speechless.

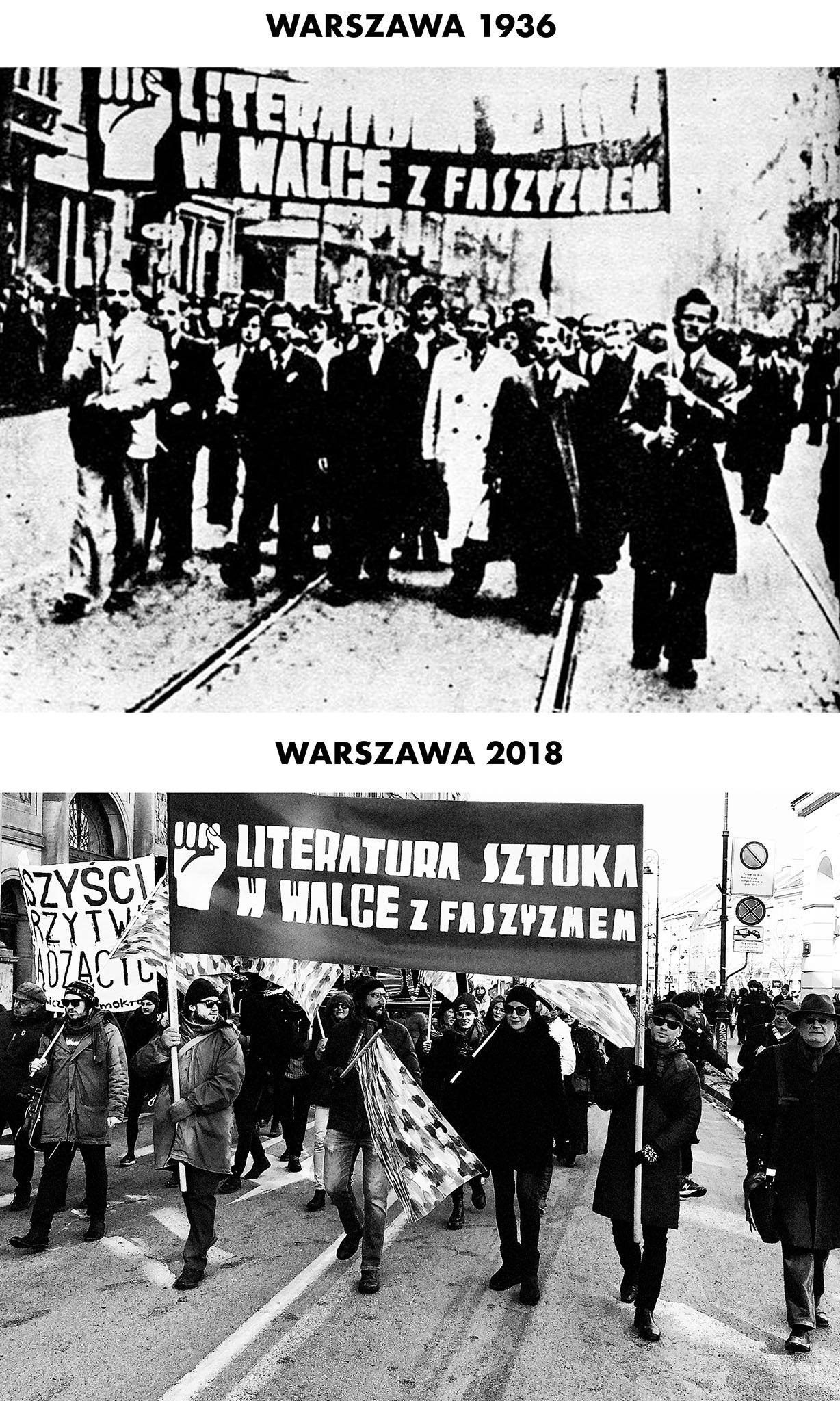

Warsaw 1936 Warsaw 2018: "literature and art against fascism" the top photo is an archival shrit from 1936 and another is a photo from reenactment we did on the antifascist demo a couple of weeks ago (collage by Witek Orski)

The good thing is that even behind the Iron Curtain, Poland tended to be the merriest barrack in the entire camp. Let us hope this continues in the future. Merriment beside, this shrit is serious. It has to de-escalate. We need to isolate real fascists from other social groups, delegitimize them, disrupt their grand narratives by showing their underlying dynamism. Call out fascism for what it is; cronyism, cynicism, manipulation, careerism, elitism and hate-mongering. Build bridges with undecided folks, support structures with comrades, transverse echo chambers, call for common decency. Otherwise, our continent could end up in even deeper shrit, as the situation can easily escalate into violence, wars, persecutions, juntas. It has not happened yet, but it is brewing. Solidarity is important, enshrining Europe as a democratic project, which it currently is not. Not fantasizing about getting rid of bad apples, lecturing or moralizing, but changing the very constitution of Europe in a progressive direction, with more accountability, democracy, equality and justice.

There is also an upbeat message. The times might be shrit, but they are fantastic for collective work with ideas and images. Three developments are important. Firstly, the art market is shrit, that is a commonly held wisdom of art activists, but now it is proofed beyond any doubts for all. Usually, the art market legitimized itself as a way of providing for artists to enjoy their creative freedoms. These claims were always rather exaggerated (and limited to few exceptions), but when the crisis came, the market simply did not provide. In countries like Hungary it proved totally unprepared to stand up to this responsibility, it simply switched to a new client base. A gallery can easily cater to the new, nationalistic bourgeoisie, just as it used to cater to the more (neo-) liberal one, a slight change in stock is enough.And how can one be blamed for doing that? Business is business. The client is always right, no? Secondly, artistic self-organization matters, just as artistic institutions do. Times of turmoil push people into uneasy alliances – like between collectives, artistic networks, unions of art workers and public art institutions – who hybridize into new artistic habitats, which can sustain art as a practice of freedom. Obviously, until the moment that they will all be pushed into the underground, but maybe such a trip to extra-institutional purgatory will not be as bad as people think. Thirdly, and the most important one, art matters again. In the market-driven circulation art was transformed into yet another commodity, one could do whatever because the content simply did not matter anyway. By weaponizing images, symbols and ideas, neo-authoritarians elevated artists and intellectuals to the plateaus from which they were evicted by market forces. These are the dialectics of our shritty times.

So the message would be: enjoy this shrit as long as it lasts. Do not long for the past, but learn from it. Accelerate and fight, before the situation devolves into something much worse. And, once again, we are all in this shrit together.

Kuba Szreder

is onderzoeker, docent en onafhankelijk curator