The long struggle

Isshaq Albarbary, Palestinian artist and researcher who is living in Amsterdam, writes a letter in response to the war in Gaza.

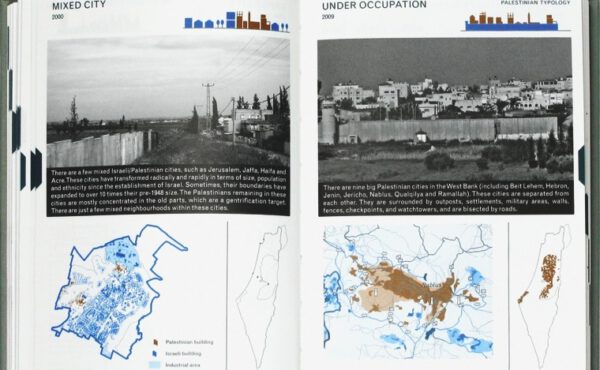

I first read Altneuland in Wadi Al-Makhrour in Beit Jala in 2014, sitting against the backdrop of the Apartheid Wall. Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, wrote this futuristic fantasy novel in 1902. My reading companion or the Wall is a 700-kilometre-long structure made of fences, concrete, watchtowers, trenches, and electronic sensors. Israel began constructing it in 2000 at the turn of the millenium and it extends across and throughout the West Bank, dividing Palestinian communities in an apartheid system and turning our neighbourhoods into isolated ghettos surrounded by Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

In the novel, Herzl envisions a future in which a Jewish state called “Neuland” (which means “new land” in German) is established in Palestine. The story follows Friedrich Loewenberg and his companion, Kingscourt, as they stumble upon this idyllic community during their voyage. The fictional land they encounter is progressive, technologically advanced, and socially just—a societywhere Indigenous Arabs and European Jews coexist peacefully.

Altneuland presented Herzl’s Zionist political ideology of establishing a national colonial project in Palestine as a final solution that would eliminate anti-Semitism in Europe forever. The novel reflects Herzl’s vision of a modern, democratic, and culturally diverse society where Jews can live freely and flourish. In his vision, the Indigenous Arabs would be happy and appreciate their colonization by European Jews because they would finally become civilized. Later, and in continuation with Herzl’s legacy, prominent Zio it’s Vladimir Zeev Jabotinsky, expanded on this ideology with an essay titled “The Iron Wall: We and the Arabs,” published in 1923 in the Russian-language Zionist journal Rassvyet (Dawn). Jabotinsky articulated the following:

“Our peace-mongers are trying to persuade us that the Arabs are either fools, whom we can deceive by masking our real aims, or that they are corrupt and can be bribed to abandon to us their claim to priority in Palestine, in return for cultural and economic advantages. I repudiate this conception of the Palestinian Arabs. Culturally they are five hundred years behind us, they have neither our endurance nor our determination; but they are just as good psychologists as we are […]We may tell them whatever we like about the innocence of our aims, watering them down and sweetening them with honeyed words to make them palatable, but they know what we want, as well as we know what they do not want. They feel at least the same instinctive jealous love of Palestine, as the old Aztecs felt for ancient Mexico, and the Sioux for their rolling Prairies.”

Almost a hundred years after Jabotinsky’s essay justifying the Iron Wall, I woke up, early on Saturday, October 7, 2023 in Amsterdam to a photo posted on social media showing a bulldozer demolishing part of the 41-kilometre-long wall that Israel built around the Gaza Strip in 1994. Reports soon began flooding in about the deadly attack launched by Hamas, a Palestinian political movement with a military wing, that led to the killing of hundreds and the capture and kidnapping of dozens of Israelis.

Gaza, often described as the largest open-air prison and concentration camp, is an area of 365 square km and home to 2.3 million Palestinians. Though it is the historic land of Palestine, it has been under an Israeli-led blockade since 2007 and Israeli administration since 1948. The worldbuilding of Herzl and Jabotinsky—as ardent admirers of the European colonial projects premised on white fascism and champions of its continuation—had deigned in their science fictions, has come to be our Palestinian present.

During this period, Western-backed genocide committed by Jewish Zionist paramilitary groups, such as the Irgun, Lehi, Haganah, and Balach, led to 750,000 to 900,000 Palestinians being forcibly displaced in Al-Nakba, or “The Catastrophe.” Over 70 per cent of Gaza’s current Palestinian population consists of refugees displaced from other parts of Palestine in 1948.

With the destruction of Palestinian society and the occupation of 78% of the land in 1948, the Zionist future culminated in establishing Israel as the homeland of the Jewish people in historic Palestine. Two decades after Israel was legalized under international law, in 1967, Israel invaded and occupied the remaining Palestinian territories, creating more refugees and camps. More than seven decades have passed, and the occupation of the land, forced displacement and ethnic cleansing against the indigenous people of Palestine has not stopped.

Following the October 7 deadly attack, Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant enforced a total blockade on Gaza, declaring, “No electricity, food, fuel, everything shut down.” He further branded the situation as a battle against “human animals,” leading to the strategic killing of 12,000 Palestinians and counting. Concurrently, Gaza witnesses hundreds of thousands and dozens in the West Bank being forcibly displaced, kidnapped, and terrorized, a continuation of the ongoing Nakba as conditioned by Zionist ideology.

Official Western narratives of history always seek to craft a polished story of progress, trying to accommodate demands for radical transformation. When Israel imposes a blockade by cutting off essential resources such as electricity, water, food and medical supplies in Gaza, there is widespread acceptance amongst politicians in North America and Europe. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asserted: “This is a struggle between the children of light and the children of darkness, between humanity and the law of the jungle, ‘promising victory to Israelis as the children of light’.” Meanwhile, Western powers unwaveringly supports Netanyahu, providing Israel with unconditional backing and weaponry and voting against a ceasefire at the UN Security Council. This support persists with the insistence by these powers that Israel remains the only democracy in the Middle East.

The apartheid system and colonial regime is enforced further through the invisible eye, an extensive surveillance infrastructure that operates discretely and subjects every corner of our lives to scrutiny by their powerful military presence. At the forefront stands Elbit Systems, Israel’s largest arms manufacturer, whose fundamental business model capitalizes on the oppression, domination, ethnic cleansing, and genocide of Palestinians.

Elbit achieves this by designing and testing advanced military technology in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip before exporting these products to the rest of the world. Elbit’s customers span the globe, such as the Dutch Army, which directly supplies parts for the F-35 fighter jets used by the Israeli Airforce in bombing Gaza.

The unconditional support for genocide reinforces a devastating hierarchy of humanity, perpetuating a dishonest political perspective that allows collective punishment to be imposed on Palestinians with alarming ease. The reality we face is a condition where Israel, whose existence and continued genocidal actions are made possible by major Western powers, maintains a permanent state of war with us—the indigenous Palestinian population.

***

I was initially asked to write this text as a letter, with the addressee printed without a return address. I think of the children of darkness, those I know and those who I will never know. Every word I write feels burdened by the weight of ongoing genocide, making every sentence an uphill struggle against the pain and despair of my people. Writing becomes an arduous task, overshadowed by the pain of seeing the suffering of my community and the ongoing injustices we face daily. Yet, if I were to write a letter, it would read as follows:

Dear reader,

While Israel is ethnically cleansing the indigenous Palestinian population, a computer chip is being reprogrammed in the Netherlands. The Dutch government refers to my nationality as ‘unknown’, and my place of birth is marked by the code ‘XXX’, as shown in the registration database system. In this obfuscated language, my identity as a Palestinian faces an existential threat, rendering me but a body in this country. Without naming, there is no Palestine. Structured in the Dutch government’s policy is an attempt to erase structures of knowledge, memory, and the history of the Palestinian struggle.

Palestinians remain caught in a nostalgia for the future lost, a constant state of anticipation for a more just future. This is why we ask: if we, the unknown, have nothing, what does the known have? And how does this ‘having’ affect deprivation? What I mean here is the deprivation of ‘stateful’ – basically, those who have nothing have both everything and nothing to lose.

Sincerely,

Isshaq Albarbary

Een Nederlandse vertaling van deze tekst is gepubliceerd in Metropolis M Nummer 6 2023/24 Host

Isshaq Albarbary

is kunstenaar en onderzoeker